-

EN

-

DE

Book a call.

Thank you! Your submission has been received!

Oops! Something went wrong while submitting the form.

If you had to pick one tissue in your body that dictates how well you age, not just how long you live, but how well you live—it would be skeletal muscle.

For decades, we were told that "cardio is for health" and "weights are for vanity." We were wrong. Modern longevity science has completely reframed how we view resistance training. It is not about building biceps for the beach; it is about building a physiological shield that protects you from the most common killers of the modern world: diabetes, frailty, and cognitive decline.

In this deep dive, we will explore the second pillar of longevity: Strength and Power. We will look at the data on why weak muscles lead to shorter lives, why "power" might be even more important than strength, and how to structure your training to build a body that lasts.

To understand why we need to train for strength, we first need to understand what we are fighting against. The enemy is Sarcopenia (from the Greek sarx for "flesh" and penia for "poverty"). It is the age-related loss of muscle mass and function.

Most of us assume that getting weaker is just a "normal" part of getting older. While some decline is natural, the rate at which it happens is largely up to us.

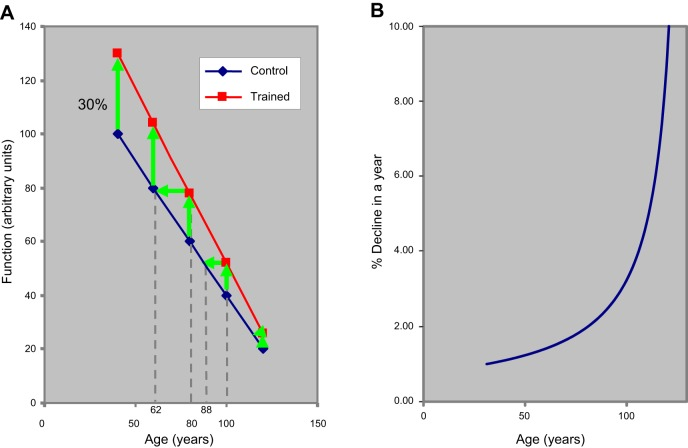

This loss isn't just about looking smaller. It’s about losing your functional independence. As the graph below illustrates, there is a specific "Disability Threshold", a minimum level of strength required for daily tasks. If you are sedentary, your trajectory crosses this line in your 70s, making you dependent on others. If you are active, you stay above it.

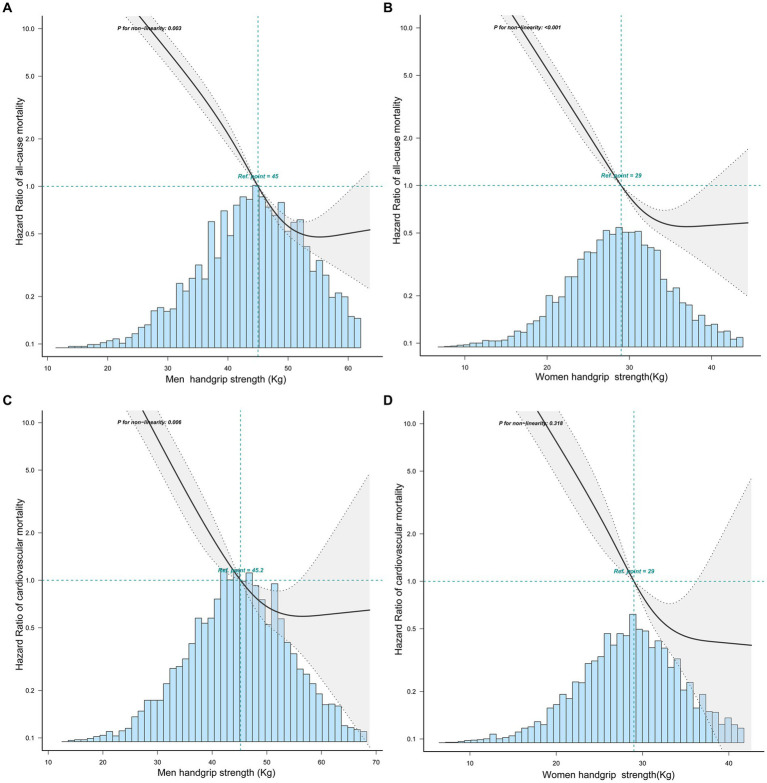

How do we measure "strength" in a medical context? We don't need you to bench press a truck. We use a simple, surprisingly powerful metric: Grip Strength.

Data from millions of people worldwide has shown that grip strength is remarkably predictive of all-cause mortality. In fact, it is often a better predictor of future health than blood pressure

Why is grip strength so important? It’s not that having strong hands magically protects your heart. It’s that grip strength is a proxy for global robustness. If you have a strong grip, it generally means you have sufficient muscle mass, a healthy nervous system, and the physical capacity to engage with the world.

We often think of organs as things like the heart, liver, or lungs. But skeletal muscle is an organ, too—an endocrine organ.

When you eat a bowl of pasta or a piece of fruit, glucose enters your bloodstream. Your body releases insulin to shuttle that glucose out of the blood and into cells. Where does it go?

In a healthy, active individual, about 80% of that glucose is disposed of in skeletal muscle.

Think of your muscles as a "metabolic sink." The larger and more active the sink, the more glucose you can safely "drain" from your bloodstream. If you lose muscle mass (sarcopenia), your sink gets smaller. The same amount of food now causes a bigger spike in blood sugar and requires more insulin to handle. Over time, this leads to insulin resistance and Type 2 Diabetes.

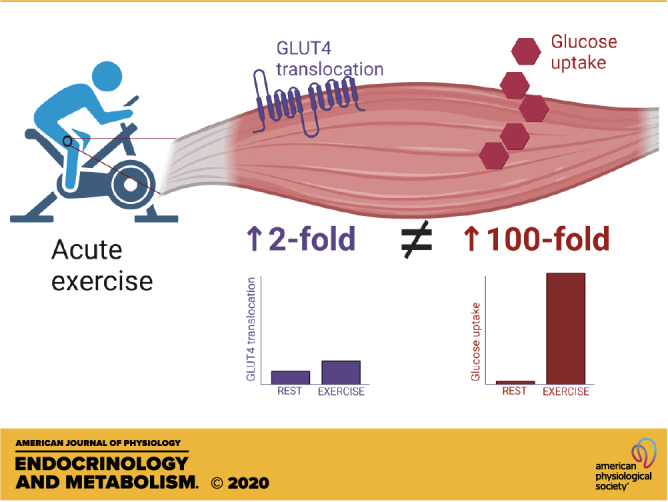

To understand how exercise opens this sink, we have to look at the cellular level. As illustrated in the classic research by Richter & Hargreaves, your muscle cells have "doors" for glucose called GLUT4 transporters.

The Critical Detail: Crucially, exercise opens these doors independently of insulin. Even if you are insulin resistant (your normal "key" is broken), the "contraction key" still works. By moving your muscles, you manually open the doors and clear glucose from your bloodstream.

The Takeaway: Building muscle is the most effective way to "buy" yourself more carbohydrate tolerance and protect your metabolic health.

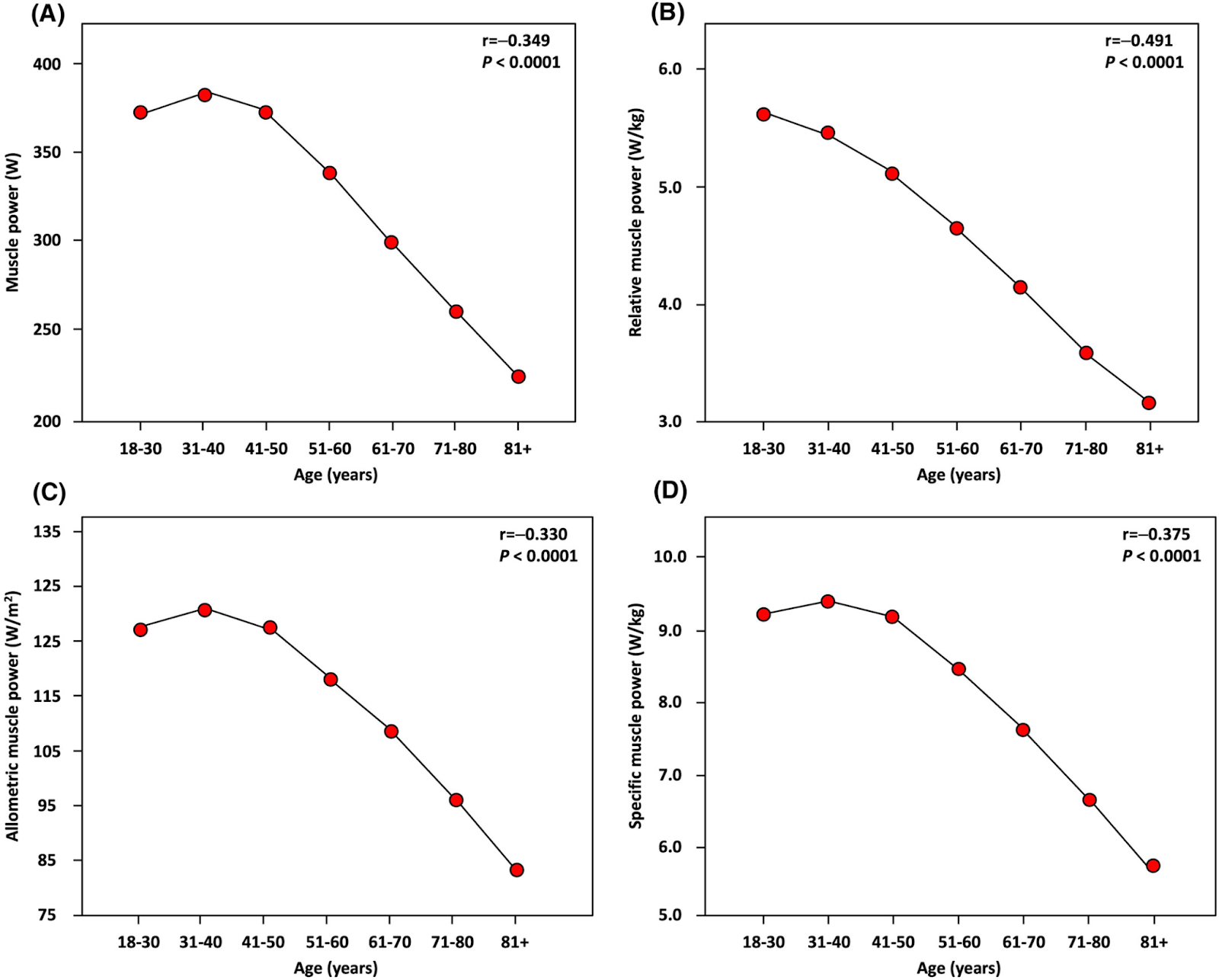

Here is a nuance that even experienced gym-goers often miss: Strength and Power are not the same thing.

Why does this matter? Because as we age, we lose power roughly twice as fast as we lose strength.

We lose our Type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibers first. These are the fibers responsible for explosive movement. You might not care about jumping high, but you should care about reaction time.

When you trip over a rug, your ability to catch yourself before you hit the ground depends on power. You need your muscles to fire instantly to shoot your leg out and stabilize your body. If you have strength but no power, you might be strong enough to hold yourself up, but too slow to get your leg in position. The result is a hip fracture—a catastrophic injury in older age.

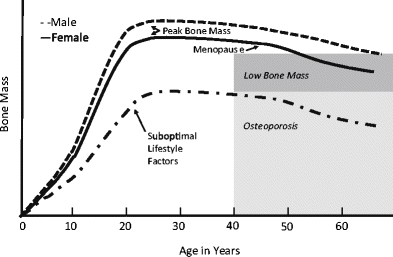

Osteoporosis is often described as "a silent killer". Peak bone mass is built in our youth, but the maintenance of that bone is a lifelong battle, especially for women.

Women start with lower bone density than men and suffer an accelerated drop in bone mass during the first 5–7 years of menopause due to the loss of estrogen.

How do we stop the drop? Bones are piezoelectric—they respond to mechanical stress by laying down more mineral density. Walking is rarely enough stress to signal this growth. To protect your bones, you need two things:

You don't need to live in the gym to build this armor. You need consistency and intensity.

Your strength program should be built around compound movements that recruit the maximum amount of muscle mass:

If you have 2-3 days a week to dedicate to strength, aim for a Full Body Split.

The most encouraging data in longevity science proves that the body retains the ability to adapt until the very end.

We see this in studies on nonagenarians (people in their 90s); when researchers put them on heavy resistance training programs, they still gained significant muscle and strength.

We also see it in the landmark LIFTMOR study (Lifting Intervention For Training Muscle and Osteoporosis Rehabilitation). In this trial, women with low bone mass—the population often told to "be careful"—were prescribed high-intensity resistance and impact training. The result wasn't an injury. It was a significant improvement in bone density and functional performance.

The LIFTMOR study dismantled the myth that older adults are too fragile to lift heavy. It proved that "fragile" bodies are exactly the ones that need heavy loading the most.

You have the capacity to build your armor at any age. The best time to start building your reserve is in your teens. The second best time is today.

Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, or prevent any medical condition. Consult with a doctor before making any changes especially if you have existing health conditions or concerns.

Citations:

Attia, P. (Host). (2023, July 10). Training for The Centenarian Decathlon: zone 2, VO2 max, stability, and strength [Audio podcast episode]. In The Peter Attia Drive. Episode #261. https://peterattiamd.com/training-for-the-centenarian-decathlon/

Coelho-Junior, H. J., et al. (2024). Sex- and age-specific normative values of lower extremity muscle power in Italian community-dwellers. Published in: Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle

Larsson, L., et al. (2019) Sarcopenia: Aging-Related Loss of Muscle Mass and Function. Published in: Physiol Rev. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00061.2017

Richter, A. E. & Hargreaves (2013): Is GLUT4 translocation the answer to exercise-stimulated muscle glucose uptake? Published in: American Journal of Physiology

Rozenberg, S., et al. (2020) How to manage osteoporosis before the age of 50 Published in: Maturitas

Watson, S. L. et al. (2018). High-Intensity Resistance and Impact Training Improves Bone Mineral Density and Physical Function in Postmenopausal Women With Osteopenia and Osteoporosis: The LIFTMOR Randomized Controlled Trial. Published in: Journal of Bone and Mineral Research