-

EN

-

DE

Book a call.

Thank you! Your submission has been received!

Oops! Something went wrong while submitting the form.

If a pharmaceutical company invented a daily pill that reduced your risk of death from all causes by nearly 400%, improved your cognitive function, regulated your blood sugar, protected your bones, and ensured you could carry your own groceries in your 80s, it would be the most valuable drug in history. It would cost a fortune, and everyone would take it.

That drug exists. It is freely available to almost everyone. It's a movement. It’s moving.

In the modern pursuit of longevity, it is easy to get distracted by supplements, biohacks, and complex protocols. Yet, the overwhelming scientific consensus is that structured exercise is the single most potent intervention we have to extend not just lifespan (how many years you live), but more importantly, healthspan (how many of those years are spent in good health, free from disability).

This guide is a foundational overview of the science of movement. We will move beyond generic advice like "walk more" and dive into the specific physiological adaptations that protect your body from aging. We will explore why cardiorespiratory fitness is a better predictor of death than smoking, why muscle is your metabolic armor, and how to structure a plan regardless of how much time you have.

Lastly, common exercise advice (like so much health advice) is based on research done on men, so this advice works on men—but not always on women. Therefore, it is important to look at exercise through gender-sensitive glasses.

What We Will Cover: To build a body that lasts, we need to train across specific components of fitness:

Most people view exercise as a way to manage weight or improve appearance or because it makes you feel good. While those are valid benefits, the longevity perspective shifts the goalpost to something far more critical: physiologic reserve.

Aging is fundamentally a process of declining capacity. Every decade after age 30, your heart’s pumping capacity, your muscle mass, and your bone density naturally decrease.

However, the demands of daily life—climbing stairs, lifting a suitcase into an overhead bin, recovering from a surgery—remain constant. If your "peak" capacity is low in midlife, it won't take long for natural aging to drag your capacity down below the threshold required for daily living.

Exercise is the only tool that raises that peak. By building a massive reserve of cardiovascular and muscular power now, you are buying insurance for your future independence. You are training not for next month's 5K, but for your "marginal decade"—the final ten years of your life. The goal is to ensure those years are spent active and engaged, not frail and housebound.

Recent large-scale studies have shown that traditional risk factors like cholesterol and smoking are secondary to a single, overarching metric: Cardiorespiratory Fitness (CRF).

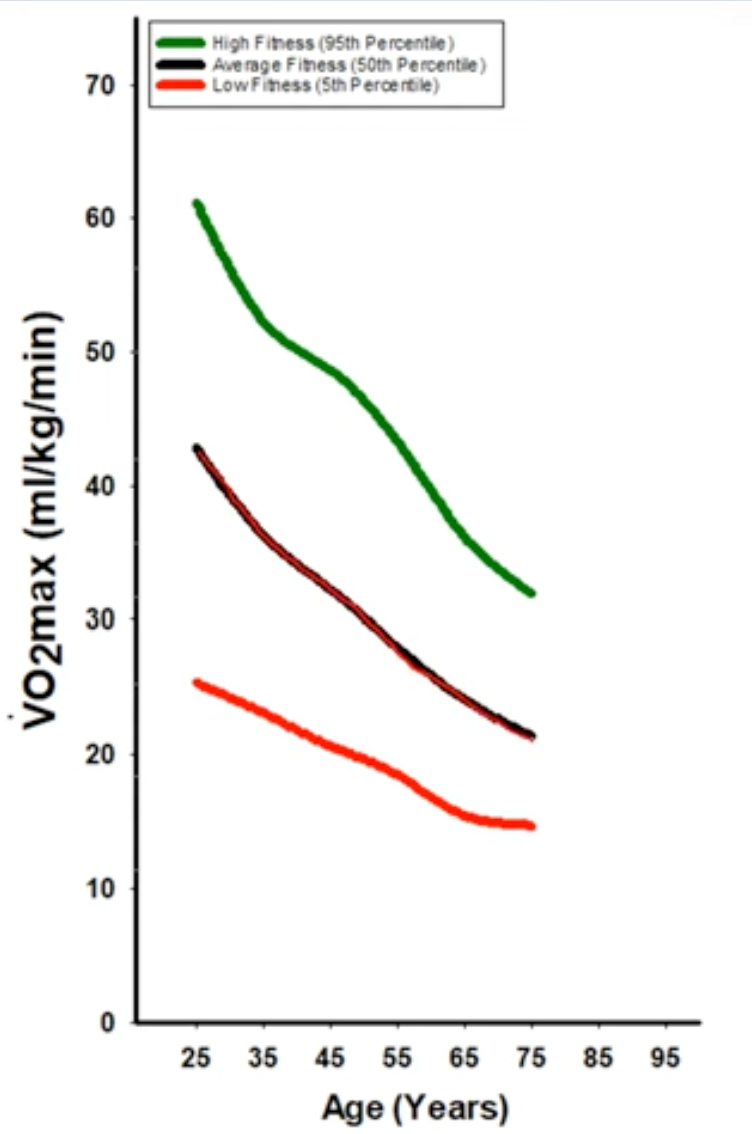

CRF is generally measured by VO2 Max—the maximum amount of oxygen your body can utilize during intense exertion. It is an "integrator" metric; for you to have a high VO2 Max, your lungs, heart, blood vessels, and muscles must all be working seamlessly together.

The data on CRF and longevity is staggering. Data consistently shows that having low cardiorespiratory fitness carries a greater risk of death than smoking, diabetes, or heart disease combined.

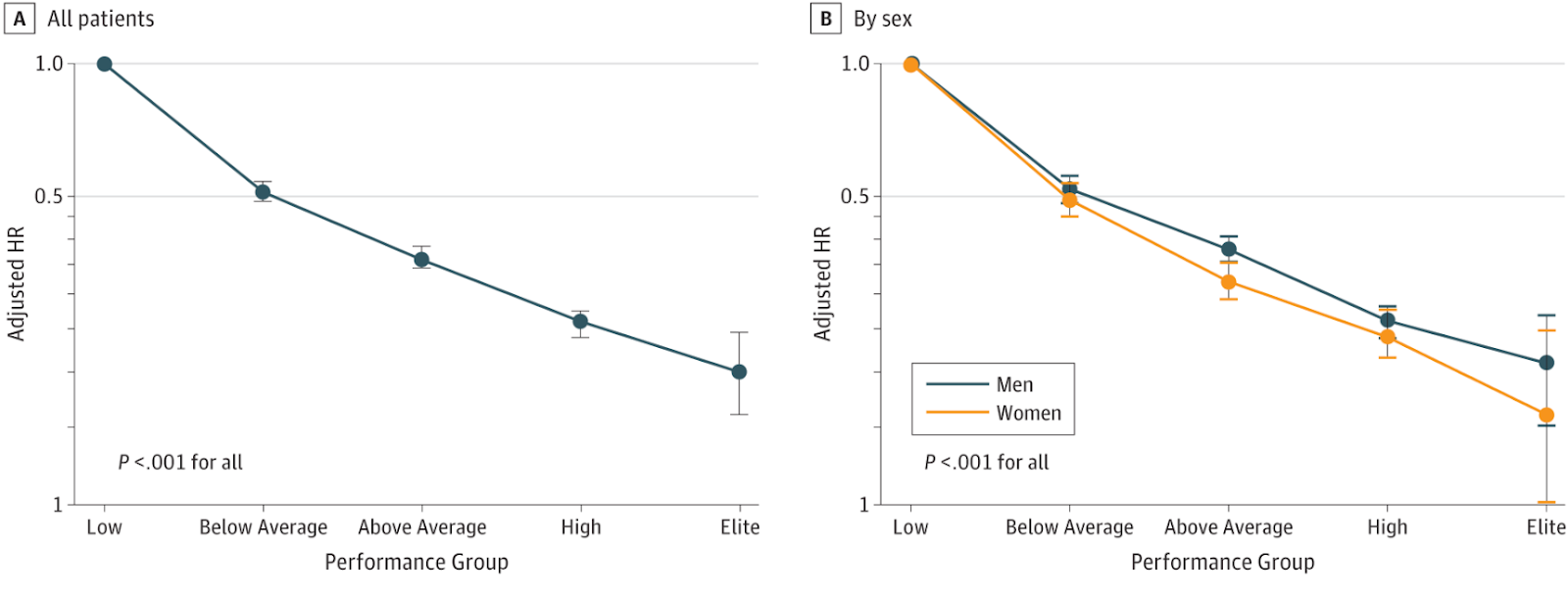

What this shows: The chart should demonstrate a dramatic, stepwise drop in mortality risk as fitness increases. The "Elite" group (top 2.5%) has roughly a 5x lower risk of death compared to the "Low" group (bottom 25%). Crucially, there is no upper limit; being "elite" is better than being just "high."

To build great cardiorespiratory fitness, think of a triangle: you need a wide base (Zone 2) to support a high peak (HIIT).

In longevity circles, "Zone 2" refers to low-to-moderate intensity, steady-state exercise. This is the intensity where your cells are maximally stressed to produce energy aerobically, primarily by burning fat. It is the level of exertion just before lactate starts accumulating in the blood.

Zone 2 is the primary driver of mitochondrial health. It increases both the number of mitochondria you have and their efficiency at turning fuel into energy.

If Zone 2 is the foundation, high-intensity training is what builds the height of the skyscraper. While you may never need your maximum output in daily life, having a high "ceiling" protects you from aging.

What this shows: Two sloping lines. One starting high (fit individual) and one starting lower (unfit individual), both declining with age. A flat horizontal line across the bottom represents the "cost of daily living" (e.g., climbing stairs). The graph shows the unfit person's capacity line crossing below the "daily living" line in their 70s, indicating loss of independence, while the fit person stays above it.

To raise your VO2 Max, you must perform training that challenges the heart's maximal pumping ability. This is best achieved through HIIT (High-Intensity Interval Training). A classic protocol is the "Norwegian 4x4": four minutes at near-maximal effort followed by four minutes of easy recovery, repeated four times.

The Time-Constraint Trade-Off: If you have limited time to train (e.g., less than 3 hours a week), you do not have the luxury of building a massive aerobic base. In this case, you should prioritize HIIT. Intensity can compensate for volume to stimulate the cardiovascular system efficiently. A recent large study with over 70,000 participants (Biswas et al., 2025) emphasized the massive impact of vigorous exercise compared to light or moderate activity. The numbers were extremely clear: 1 minute of vigorous activity provided the same mortality risk reduction as roughly 4 minutes of moderate activity, and nearly 9 minutes for preventing diabetes. This confirms that when time is short, "going hard" is a mathematical multiplier for your health.

Skeletal muscle is a critical organ for longevity. It acts as your primary "metabolic sink"—when you eat carbohydrates, about 80% of the glucose goes into your muscle tissue (if you have enough of it). This means that maintaining muscle mass is your primary defense against insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

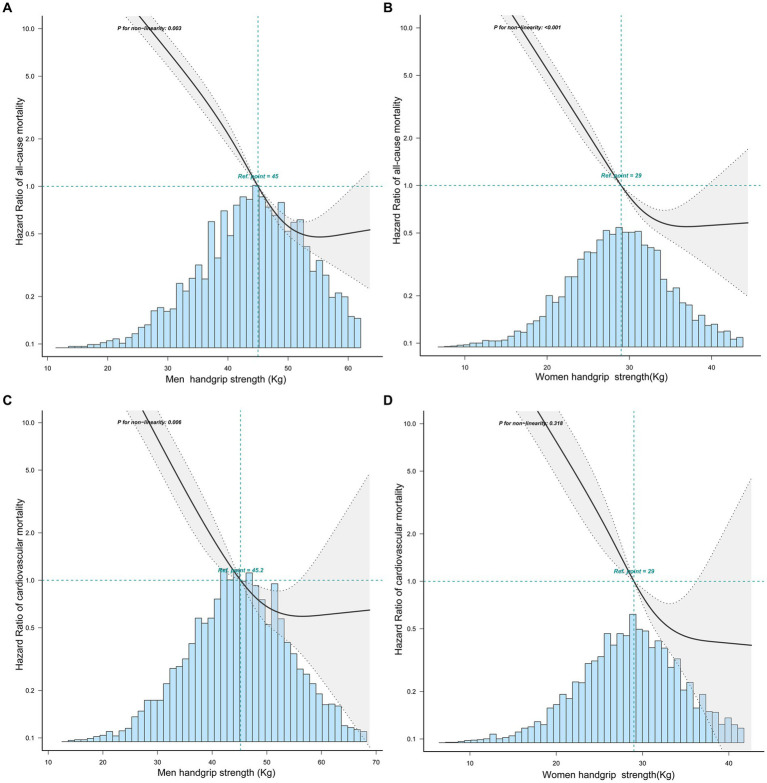

Furthermore, strength is the physical armor that protects you from frailty. Data shows that grip strength is remarkably predictive of future health and mortality.

What this shows: The data consistently shows a J-curve: lower grip strength correlates with a significantly higher risk of mortality and adverse health events. Every kilogram of strength lost corresponds to an uptick in risk.

It’s not just about raw strength (how much you can lift); it’s also about power (how fast you can lift it). Aging preferentially destroys fast-twitch muscle fibers, which are responsible for explosive movement. Power is what allows you to catch yourself before you fall when you trip over a curb. Incorporating faster, explosive movements is critical for preventing catastrophic falls.

While cardio and strength are the engines and armor, stability and flexibility are the chassis. Without them, the risk of injury increases, potentially sidelining you from the very exercises that keep you young. Incorporating balance training and maintaining flexibility ensures that you can utilize your strength safely and effectively into your later years.

Understanding the pillars of cardiorespiratory fitness, strength, and protein is the theory. Applying it to a busy life is the practice.

The most common barrier to exercise is time. The good news is that exercise physiology allows for trade-offs. The fundamental rule of training programming is: When volume is low, intensity must be high.

If you have unlimited time, you can build tremendous fitness doing hours of low-intensity Zone 2 work. If you are a busy parent or professional with only three hours a week to train, you do not have that luxury. You must prioritize intensity to elicit a physiological stimulus.

Here is a general framework for how training focus shifts based on time availability:

Prioritize Intensity & Strength. You don't have time for a huge aerobic base. Use High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) to stimulate the cardiovascular system efficiently and prioritize resistance training to protect muscle.

• 2x 30-min Full Body Strength

• 2x 30-min HIIT sessions

The Balanced Approach. This allows for the "gold standard" mix. You have enough time to build a Zone 2 foundation while still hitting strength and high-intensity peaks.

• 3x 45–60 min Zone 2 cardio

• 2x 60-min Strength training

• 1x VO2 Max interval session (often combined at the end of a Zone 2 session)

Maximize Volume. This resembles elite endurance training. The vast majority of time is spent in Zone 2 to manage fatigue, supporting hard strength and VO2 Max

• 4–5x Zone 2 sessions (some long)

• 3x Strength sessions

• 1–2x Hard Interval sessions

Because so much research is male-centric, women need to pay attention to specific nuances in training and fueling:

Building a body designed for longevity is not about chasing short-term performance goals. It is about preparation.

The training you do today is preparation for your 80s. Every session of Zone 2 builds efficiency for a future where energy is scarcer. Every heavy lift and jump builds a reserve of strength to prevent a fall. The science is clear: exercise is the most potent preventive medicine available.

You are training for your last decades of your life. The goal is to ensure those years are spent active and engaged, not frail and housebound.

Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes only and is not intended to diagnose, treat, or prevent any medical condition. Consult with a doctor before making any changes especially if you have existing health conditions or concerns.

Citations:

Attia, P. (Host). (2023, July 10). Training for The Centenarian Decathlon: zone 2, VO2 max, stability, and strength [Audio podcast episode]. In The Peter Attia Drive. Episode #261. https://peterattiamd.com/training-for-the-centenarian-decathlon/

Biswas, R. K., et al. (2025). Wearable device-based health equivalence of different physical activity intensities against mortality, cardiometabolic disease, and cancer. Published in: Nature Communications.

Gifford et al. (2016). The physiological reserve to do daily activities.

Mandsager et al. (2018): Association of Cardiorespiratory Fitness with Long-term Mortality Among Adults Undergoing Exercise Treadmill Testing. Published in JAMA Network Open.

Phillips et al. (2016): Protein "requirements" beyond the RDA: implications for optimizing health and active aging. Published in Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism.

Roschel et al. (2021). Creatine Supplementation and Brain Health. Published in Nutrients.

Wisløff et al. (2007): Superior Cardiovascular Effect of Aerobic Interval Training Versus Moderate Continuous Training in Heart Failure Patients. Published in Circulation.

Xiong et al. (2023): The association of handgrip strength with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database prospective cohort study with propensity score matching. Published in Frontiers in Nutrition.